The perceptive among you will notice I’ve attempted to write this before. This is a complete rewrite and I’m much happier with it now. Enjoy!

I am the kind of person who really enjoyed The Witness. Its quiet world and slow pace managed to set a new, calmer baseline for what counts as exciting in a world where our demand for stimulus is increasingly high. That’s why I was excited when I found out about In Other Waters. It was one of those games where I went to watch someone play it and stopped immediately – I wanted the experience for myself.

By that point, I had been a climate activist for a year or so, working on projects at my school and as part of national campaigns. There are lots of ways to try and change policy. We tend to see activism as lying on a scale from acceptable and status-quo-maintaining to radical and disruptive. I’ve wanted to do everything on that scale at some point. Since I am often part of the less disruptive actions, I have been learning how to hold two disparate goals in my head: what I want to do, and what I would do. There is an important distinction between the better world I want to build, and the first steps I would really take to get there.

Sometimes I wake up and for a long moment convince myself that the Earth’s crises can’t really be a problem, that we’ve got it under control, and I’ve massively exaggerated how bad the situation we’re in is. Those are in some ways my most hopeless moments, because afterwards I feel sick and sad and terrified, having noticed the scale of the crisis we’re in. I hold strongly that people are generally good, but the scale of global boiling continually clashes with that belief.

Being a climate activist is not a position that sits well with my unconscious assumption that I am the main character of the universe: that if I do nothing wrong, the universe should leave me alone. None of us are main characters, but we each see the world from our individual perspective so it’s something we assume without noticing.

The fact that I can wake up thinking everything’s going to be alright is partially a consequence of the perspective I generally approach environmental issues from. My efforts may be futile, but I’d rather be a fool and try anyway than be sensible and give up.

In Other Waters is a game about exploring Gliese 667Cc, a real exoplanet with a chance of harbouring life. It has a minimal 2D art style, and descriptions of how the world looks are the written observations of Dr Ellery Vas.

There is life on Gliese 667Cc. There is a rich underwater ecosystem filled with undiscovered species. One scientist exploring them for a handful of days barely scratches the surface of the new plants, fungi, animals, and bacteria present. Ellery is extremely curious and asks a lot of questions, but they almost universally go unanswered – not for lack of effort, but because that’s what science is like.

Except life on Gliese 667Cc is not quite undiscovered: against regulation, Baikal, a company looking for resources on exoplanets, has already attempted to exploit the planet’s most advanced form of life, the Artificers, and in doing so nearly destroyed the ecosystems we learn about in the game.

In Other Waters is minimal graphically, so the sound and writing take on the role of showing us Gliese 667Cc. In doing so, they create an extremely compelling image of this world.

The shallows are the realm of the stalks. Together they form communities connected by a nuanced chemical language. These colonies even have relationships with the lively Spore Catchers which flit, camouflaged, among the stalks. In the deep ocean, great Brine Striders wander unhurriedly across the ocean floor. The unique collection of bioluminescent bacteria which each carries lights up in the darkness. Nearby, deep orreries cast their intricate, ever-changing veils over the seabed. In the even more hostile environment of the Bloom, the area contaminated by Baikal’s experiments, life has adapted rapidly and effectively to the new habitat. Bivalve Bloomvanes wait in the silt banks until the toxic soup allows for a brief frenzy of feeding. Deep within the Bloom, great Emerald Bloomfins move cautiously, filtering the bacterial sludge for nutrients.

The game does not give explicit rewards for exploration. Much like The Witness, there is no fanfare and there are no tech trees to progress. Much like The Witness, In Other Waters was criticised for a lack of rewards and variation in gameplay. Unlike The Witness, In Other Waters uses this not only to set our expectations, but to encourage us to use our imaginations and accept what we learn about the world as the reward.

In Other Waters asks us to be curious, and gives us space to marvel at the complexities of life. In fact, Gareth Damian Martin – the one-person studio behind the project – said that one of their goals for In Other Waters was to create a game about these moments of wonder.

I was absorbed by the small part of Gliese 667Cc we see in In Other Waters: I poured over Ellery’s descriptions, marvelled at her sketches, and I was fascinated by how these species might live, feel, and communicate. The consequences of Baikal’s recklessness may be small on the scale of a world, or even insignificant on the scale of a Galaxy, but I was still in awe of their impact.

In the end, however, the assemblages in In Other Waters are not real – the Earth and everything on it certainly are.

In Other Waters seems to come from a place of deep appreciation for the Earth and the inherent value of living things. What Gareth showed me was that there can be a reason to fight the planet’s crises that isn’t predicated on quantifications of lives lost or economic value destroyed. A reason to fight that acknowledges something that people closer to the Earth have known forever: that what we see around us is special, and infinitely deserving of curiosity.

As I was beginning this realisation and process of learning, which is still very much underway, ‘Symbiosis’, the final piece in In Other Waters’s soundtrack was playing. This piece perfectly captures symbiosis, where life has mutually beneficial relationships with other life. Call and response forms the basis of the score. The melodies, which often have little sense of rhythm, are picked up by different voices and returned. ‘Symbiosis’ is the pinnacle of this: it gives the sense of the ecosystems we’ve seen so far, not just calling and responding, but harmonising in a way that is hard to quantify but obviously present. In contrast, the locations where Baikal has tried to exploit life have had their rhythms and melodies wrenched into bars. There is still life here and it still responds, but only to the jagged sounds of machinery. Where I heard beauty, Baikal heard something that could be made more efficient.

In Other Waters brought my attention to symbiosis not just on Gliese 667Cc, but on Earth too. To me, it is profoundly beautiful to begin to see all the ways that life exists only because it exists. This game forms a small part of everything I’ve engaged with to learn more about people and the climate crisis. It is special to me, because it allowed me to pause and reflect on the value of things.

Rivers are now being given legal personhood, and there is a growing movement to recognise ecocide as a crime under international law; yet legal changes alone will not create the mindset change required to save life on Earth. The Earth is a gift. Her oil and her wood are not made valuable when we extract them, but are gifts from the fish and the trees that made them. We’ve been trained well to think about the Earth as a mechanism, but assemblages of life exist at scales that reject this mechanistic view of the world. Traditional Western thinking may say how much money a rainforest is worth, but it struggles to discard that valuation and recognise it as a collection of beings. This static mindset was necessary to justify the genocide of indigenous people and erasure of cultures, which both formed a fundamental part of colonialism.

Despite our exploitation, the Earth remains, and she still has lessons to teach us. People who have that emotional connection to nature are better able to listen to her, and that’s what In Other Waters opened me up to. It becomes impossible to regard the forest you grew up next to as only a resource for tourism and recreation, and it becomes obvious to see the mosses and trees as teachers, deserving life simply by being.

One problem with explanations of different ways of conceptualising the world is that they are either incredibly simple or extremely messy. There are some wonderful attempts at explanations of other perspectives by people with much more experience than me, such as Robin Wall Kimmerer and Amitav Ghosh. I have been fundamentally changed by learning about how different people think of the Earth and I can’t recommend their works enough. It is always art that reveals different ideas – read a book or play a video game, I don’t mind.

There is no future without us imagining it first, that is what I learnt here. Gliese 667Cc was a test of our imaginations, of our ability to see things differently, to do things differently to the way things had always been done.

We needed to change our methods of study, our relationship to our surroundings, our understanding of communication, of sentience, of life. Each of those was an imaginative act, a leap we had to take to realise something new.

And yet, all those answers were already there, already present on our own planet, in our own time, we just needed to imagine them.

[GDM//2254]

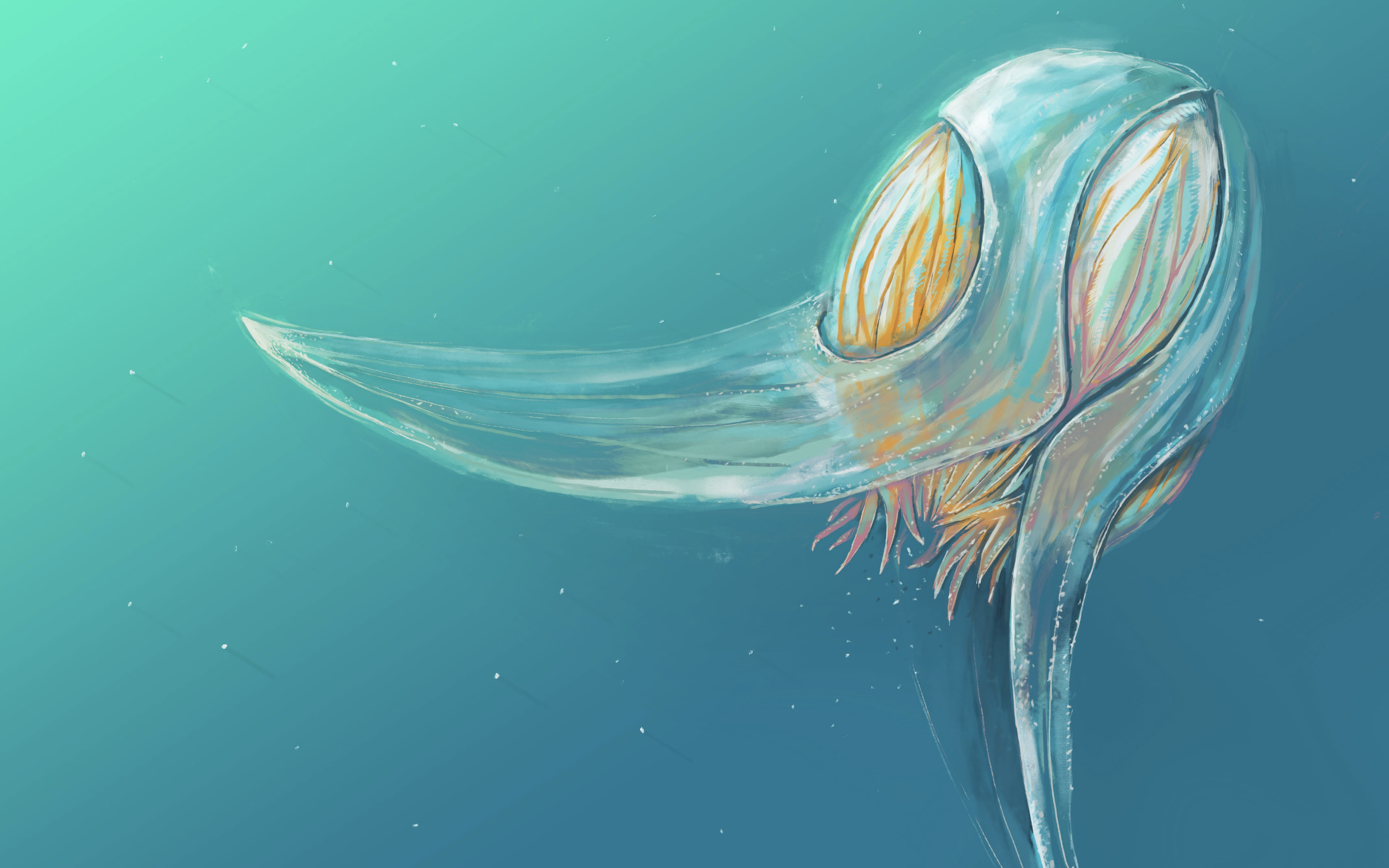

A FEEDING DRIFTWING FLOATS PLACIDLY BY DR. ELLERY VAS // 2218

A FEEDING DRIFTWING FLOATS PLACIDLY BY DR. ELLERY VAS // 2218

Quotes and images from A Study of Gliese 667Cc by Gareth Damian Martin, the epilogue to In Other Waters. Banner photo from In Other Waters.

Thanks,

Oscar Mitcham